You are here

Plants

Mandragora officinarum

EOL Text

Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLDS) Stats

Public Records: 6

Specimens with Barcodes: 6

Species With Barcodes: 1

Mandragora officinarum or mandrake is the type species of the plant genus Mandragora, native to Europe and Mediterranean region. It is a perennial herbaceous plant with ovate leaves, white to purple flowers, which produce red berries. It is also called autumn mandrake or Mediterranean mandrake.[2]

Because mandrake contains deliriant hallucinogenic tropane alkaloids and shape of its roots often resembles human figures, it has been associated with a variety of superstitious practices throughout the history. It has long been used in magic rituals, today also in contemporary pagan traditions such as Wicca and Odinism. [3]

Contents

Physical characteristics[edit]

Mandrake is a perennial plant growing to 0.1 by 0.3 m (0.33 by 0.98 ft). It is in leaf from late winter to midsummer, in flower from late winter through early spring, and the seeds ripen in late summer.[dubious – discuss] The flowers are hermaphroditic (have both male and female organs) and are pollinated by insects. The plant is self-fertile.

The roots are somewhat carrot-shaped and can be up to 1.2 m (3.9 ft) long; they often divide into two and are vaguely suggestive of the human body. This root gives off at the surface of the ground a rosette of ovate-oblong to ovate, wrinkled, crisp, sinuate-dentate to entire leaves, 5 to 40 cm (2.0 to 15.7 in) long, somewhat resembling those of the tobacco plant. A number of one-flowered nodding peduncles spring from the neck bearing whitish-green or purple flowers, nearly 5 cm (2.0 in) broad, which produce globular, orange to red berries, resembling small tomatoes. The fruit and the seeds are poisonous.[4]

Leaves grow in a rosette, and are ovate-oblong to ovate, wrinkled, crisp, sinuate-dentate to entire leaves, 5 to 40 cm (2.0 to 15.7 in) long, somewhat resembling those of the tobacco plant. A number of one-flowered nodding peduncles spring from the neck bearing whitish-green or purple flowers, nearly 5 cm (2.0 in) broad, which produce globular, orange to red berries, resembling small tomatoes. All parts of the plant are poisonous. The plant grows natively in southern and central Europe and in lands around the Mediterranean Sea, as well as on Corsica.

The plant requires well-drained, acidic or neutral soils; it prefers light (sandy) and medium (loamy) ones. It can grow in semi-shade (light woodland) or no shade. It grows in woodlands, cultivated beds, sunny edges, and dappled shade in locations where temperature never drops under about -15°C.

Effects[edit]

The alkaloid chemicals contained in the root include atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine. These chemicals are anticholinergics, hallucinogens, and hypnotics. Anticholinergic properties can lead to asphyxiation. Ingesting mandrake root is likely to have other adverse effects such as vomiting and diarrhea. The alkaloid concentration varies between plant samples, and accidental poisoning is likely to occur.[5]

Folklore[edit]

Mandrake has a long history of medicinal use, although superstition has played a large part in the uses to which it has been applied. It is rarely prescribed in modern herbalism.[citation needed]

The fresh or dried root contains highly poisonous alkaloids, including atropine, hyoscyamine, scopolamine, scopine, and cuscohygrine.[6] The root is hallucinogenic and narcotic. In sufficient quantities, it induces a state of oblivion and was used as an anaesthetic for surgery in ancient times.[7] In the past, juice from the finely grated root was applied externally to relieve rheumatic pains.[7] It was also used internally to treat melancholy, convulsions, and mania.[7] When taken internally in large doses, however, it is said to excite delirium and madness.[7]

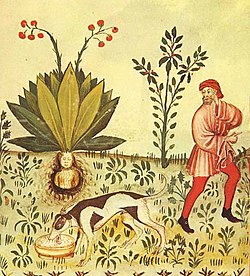

In the past, mandrake was often made into amulets which were believed to bring good fortune, cure sterility, etc. In one superstition, people who pull up this root will be condemned to hell, and the mandrake root would scream as it was pulled from the ground, killing anyone who heard it.[3] Therefore in the past, people have tied the roots to the bodies of animals and then used these animals to pull the roots from the soil.[3]

In the Bible[edit]

Two references to דודאים (dûdã'im)—literally meaning "love plant"—occur in the Jewish scriptures. The Septuagint translates דודאים (dûdã'im) as μανδραγόρας (mandragoras), and Vulgate follows Septuagint. A number of later translations into different languages follow Septuagint (and Vulgate) and use mandrake as the plant as the proper meaning in both Genesis 30:14–16 and Song of Solomon 7:13. Others follow the example of the Luther Bible and provide a more literal translation.

In Genesis 30:14, Reuben, the eldest son of Jacob and Leah finds mandrake in a field. Rachel, Jacob's infertile second wife and Leah's sister, is desirous of the דודאים and barters with Leah for them. The trade offered by Rachel is for Leah to spend that night in Jacob's bed in exchange for Leah's דודאים. Leah gives away the plant to her barren sister, but soon after this (Genesis 30:14–22), Leah, who had previously had four sons but had been infertile for a long while, became pregnant once more and in time gave birth to two more sons, Issachar and Zebulun, and a daughter, Dinah. Only years after this episode of her asking for the mandrakes did Rachel manage to become pregnant. The predominant traditional Jewish view is that דודאים were an ancient folk remedy to help barren women conceive a child.[citation needed]

14 And Reuben went in the days of wheat harvest, and found mandrakes in the field, and brought them unto his mother Leah. Then Rachel said to Leah, Give me, I pray thee, of thy son's mandrakes.

15 And she said unto her, Is it a small matter that thou hast taken my husband? and wouldest thou take away my son's mandrakes also? And Rachel said, Therefore he shall lie with thee to night for thy son's mandrakes.

16 And Jacob came out of the field in the evening, and Leah went out to meet him, and said, Thou must come in unto me; for surely I have hired thee with my son's mandrakes. And he lay with her that night.

A number of other plants have been suggested by biblical scholars,[citation needed]e.g., most notably, ginseng, which looks similar to the mandrake root and reputedly has fertility enhancing properties, for which it was picked by Reuben in the Bible; blackberries, Zizyphus lotus, the sidr of the Arabs, the banana, lily, citron, and fig. Sir Thomas Browne, in Pseudodoxia Epidemica, ch. VII, suggested the dudai'im of Genesis 30:14 is the opium poppy, because the word duda'im may be a reference to a woman's breasts.

The final verses of Song of Songs (Song of Songs 7:12–13), are:

לְכָ֤ה דֹודִי֙ נֵצֵ֣א הַשָּׂדֶ֔ה נָלִ֖ינָה בַּכְּפָרִֽים׃ נַשְׁכִּ֙ימָה֙ לַכְּרָמִ֔ים נִרְאֶ֞ה אִם פָּֽרְחָ֤ה הַגֶּ֙פֶן֙ פִּתַּ֣ח הַסְּמָדַ֔ר הֵנֵ֖צוּ הָרִמֹּונִ֑ים שָׁ֛ם אֶתֵּ֥ן אֶת־דֹּדַ֖י לָֽךְ׃

12 Let us get up early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine flourish, whether the tender grape appear, and the pomegranates bud forth: there will I give thee my loves.

13 The mandrakes give a smell, and at our gates are all manner of pleasant fruits, new and old, which I have laid up for thee, O my beloved.

Magic and witchcraft[edit]

According to the legend, when the root is dug up, it screams and kills all who hear it. Literature includes complex directions for harvesting a mandrake root in relative safety. For example Josephus (circa 37–100 AD) of Jerusalem gives the following directions for pulling it up:

A furrow must be dug around the root until its lower part is exposed, then a dog is tied to it, after which the person tying the dog must get away. The dog then endeavours to follow him, and so easily pulls up the root, but dies suddenly instead of his master. After this, the root can be handled without fear.[10]

Excerpt from Chapter XVI, "Witchcraft and Spells", of Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual by nineteenth-century occultist and ceremonial magician Eliphas Levi.

The following is taken from Paul Christian's The History and Practice of Magic:[11]

Would you like to make a Mandragora, as powerful as the homunculus (little man in a bottle) so praised by Paracelsus? Then find a root of the plant called bryony. Take it out of the ground on a Monday (the day of the moon), a little time after the vernal equinox. Cut off the ends of the root and bury it at night in some country churchyard in a dead man's grave. For 30 days, water it with cow's milk in which three bats have been drowned. When the 31st day arrives, take out the root in the middle of the night and dry it in an oven heated with branches of verbena; then wrap it up in a piece of a dead man's winding-sheet and carry it with you everywhere.

In literature[edit]

In its more sinister significance:

- Machiavelli wrote in 1518 a play Mandragola (The Mandrake) in which the plot revolves around the use of a mandrake potion as a ploy to bed a woman.

- Shakespeare refers four times to mandrake and twice under the name of mandragora.

- "... Not poppy, nor mandragora,

- Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world,

- Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep

- Which thou owedst yesterday."

- Shakespeare: Othello III.iii

- "Give me to drink mandragora ...

- That I might sleep out this great gap of time

- My Antony is away."

- Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra I.v

- "Shrieks like mandrakes' torn out of the earth."

- Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet IV.iii

- "Would curses kill, as doth the mandrake's groan"

- King Henry VI part II III.ii

- John Donne refers to it in the second line of his song, 'Go and catch a falling star', as an example of an impossible task,

- "Get with child a mandrake root"

- Alraune (German for Mandrake) is a novel by German novelist Hanns Heinz Ewers published in 1911.

- It is in Samuel Beckett's Waiting For Godot, too. "Let's hang ourselves immediately!" "It'd give us an Erection!" "An Erection!" "With all that follows—where it falls, Mandrakes grow, that's why they shriek when you pull them up. Did you not know that?"

- In Harry Potter by J.K. Rowling, mandrakes can be found in the Hogwarts greenhouses. When pulled out of the earth, they resemble humans, and just as in the mythology, the cry is fatal. The mandrake can also revive those who have been petrified.

- In The Winter of Our Discontent by John Steinbeck, Ethan Hawley mentions both the form and legend of the mandrake root in chapter eight when describing a collection of "worthless family treasures" as follows: "We even had a mandrake root—a perfect little man, sprouted from the death-ejected sperm of a hanged man ..."

- In Pan's Labyrinth by Guillermo del Toro, the Fawn, Pan, explains that a mandrake root is "A plant that dreamt of being human", and it can have healing powers if instructions are followed.

- In Equal Rites by Terry Pratchett, a reference to the mandrake is made, describing a plant that lets out a supersonic scream when it is uprooted.

- In Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Adventure of the Devil's Foot (contained in the Sherlock Homes collection His Last Bow) a crystalline extract of "Devil's Foot Root", also called mandrake, is at the root, so to speak, of two bizarre and related murders.

- In Neil Gaiman's "The Ocean at the End of the Lane" Lettie Hempstock trades a Mandrake for a shadow-bottle to attempt to send Ursula Monkton away "Mandrakes are so loud when you pull them up, and I didn't have earplugs"

- In The Republic by Plato, mandrake is used in an image whereby men use it to drug a ship captain, and take control of the ship (488 c4).

References[edit]

- ^ Ungricht, Stefan; Knapp, Sandra & Press, John R. (1998). "A revision of the genus Mandragora (Solanaceae)". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum (Botany Series) 28 (1): 17–40. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- ^ "USDA GRIN Taxonomy". Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ a b c John Gerard (1597). "Herball, Generall Historie of Plants". Claude Moore Health Sciences Library.

- ^ Mandrake in wildflowers of Israel

- ^ Piccillo, G.A.; Mondati, E.G.M.; Moro, P.A. (2002). "Six clinical cases of Mandragora autumnalis poisoning: diagnosis and treatment". European Journal of Emergency Medicine 9 (4): 342–347. doi:10.1097/00063110-200212000-00010.

- ^ Hanuš, Lumír O.; Řezanka, Tomáš; Spížek, Jaroslav; Dembitsky, Valery M. (2005). "Substances isolated from Mandragora species". Phytochemistry 66 (20): 2408–17. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.07.016. PMID 16137728.

- ^ a b c d A Modern Herbal, first published in 1931, by Mrs. M. Grieve, contains Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-Lore.

- ^ "Genesis 30:14–16 (King James Version)". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "Song of Songs 7:12–13 (King James Version)". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ James Hastings (October 2004). A Dictionary of the Bible: Volume III: (Part I: Kir -- Nympha). University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 978-1-4102-1726-4. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ pp. 402-403, by Paul Christian. 1963

Further reading[edit]

- Heiser, Charles B. Jr (1969). Nightshades, The Paradoxical Plant, 131-136. W. H. Freeman & Co. SBN 7167 0672-5.

- Thompson, C. J. S. (reprint 1968). The Mystic Mandrake. University Books.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mandragora_officinarum&oldid=654810602 |